As mentioned, I am reviving the Stella series with a fourth book! For those who have not read the first three books, I’ll share excerpts, nuggets, and tidbits as we prepare for the fourth installment. Today, we are refamiliarizing ourselves with some of the family. Enjoy!

Stella May

Born in 1845, Stella is the daughter of a Black woman named Deborah on Paul Saddler’s Plantation in Shreveport, Louisiana. From a young age, she can remember running through cotton fields and being loved by her family. To young Stella, life is simple and fun. She eats sweet cakes, plays with her friend Carla, and helps the grownups by carrying buckets of water to the field. Stella discovers she is a slave for the first time after Deborah’s unexplained death. Now, she learns the hard way the difference between slavery and freedom.

Solomon Curtis May

Solomon has no speaking roles, but his existence is essential for the family timeline. Solomon Curtis May is Stella’s only son, born in the fall of 1870 after she was sexually assaulted by the husband of her mistress. Solomon falls in love with a white woman and marries her after inheriting land outside Chicago. They have four girls: Deborah, named for his grandmother, Judith, Rebecca, and Sara.

Judith May

Solomon’s daughter Judith married a Black man and gave birth to a baby girl she named Stella after her grandmother. However, after enduring much teasing and discrimination for her mixed features, Judith’s daughter copes with this trauma by denying part of her ancestry. She changes her name from Stella to Sidney McNair and passes for white. After marrying a white man and having his children, Sidney lives her life on the other side of the color line.

Sidney McNair

Her aunt Sara influenced Sidney to pass for white and learn to enjoy her privileges. Sidney marries a wealthy white man named Clarence McNair, and they have four children: Edward, Karen, Joseph, and Glenda, whom they raise as white.

However, when she finally reveals the truth to her adult children in 1979, the shock of their real identity is a betrayal that stretches across generations.

Karen and Noah

Sidney’s daughter Karen McNair falls in love with a young Black man named Noah Daniels. He is a leading member of the Black Panther Party and thinks he’s dating a white girl. At this time, Karen also does not know that she is mixed race, although she has many more African American features than her siblings. The couple endures many trials because of their perceived interracial union. Together, they have a son, Noah Jr, who has a much more significant role as an adult in book four.

Edward McNair

Of all Sidney’s children, her sons are the most conflicted by their mother’s betrayal. Carrying many characteristics of his father, Clarence, Edward has not only lived his life as a white man but has also enjoyed the privileges of doing so and cannot come to grips with his new reality. In brief, Edward does not want to be Black, and his daughter, Cynthia, does not yet know about her true identity because of her father’s secrets.

However, although he appears to reject his heritage, something in Edward’s subconscious won’t allow him to completely forget it. We see this when he names his youngest son after his great-grandfather, Solomon.

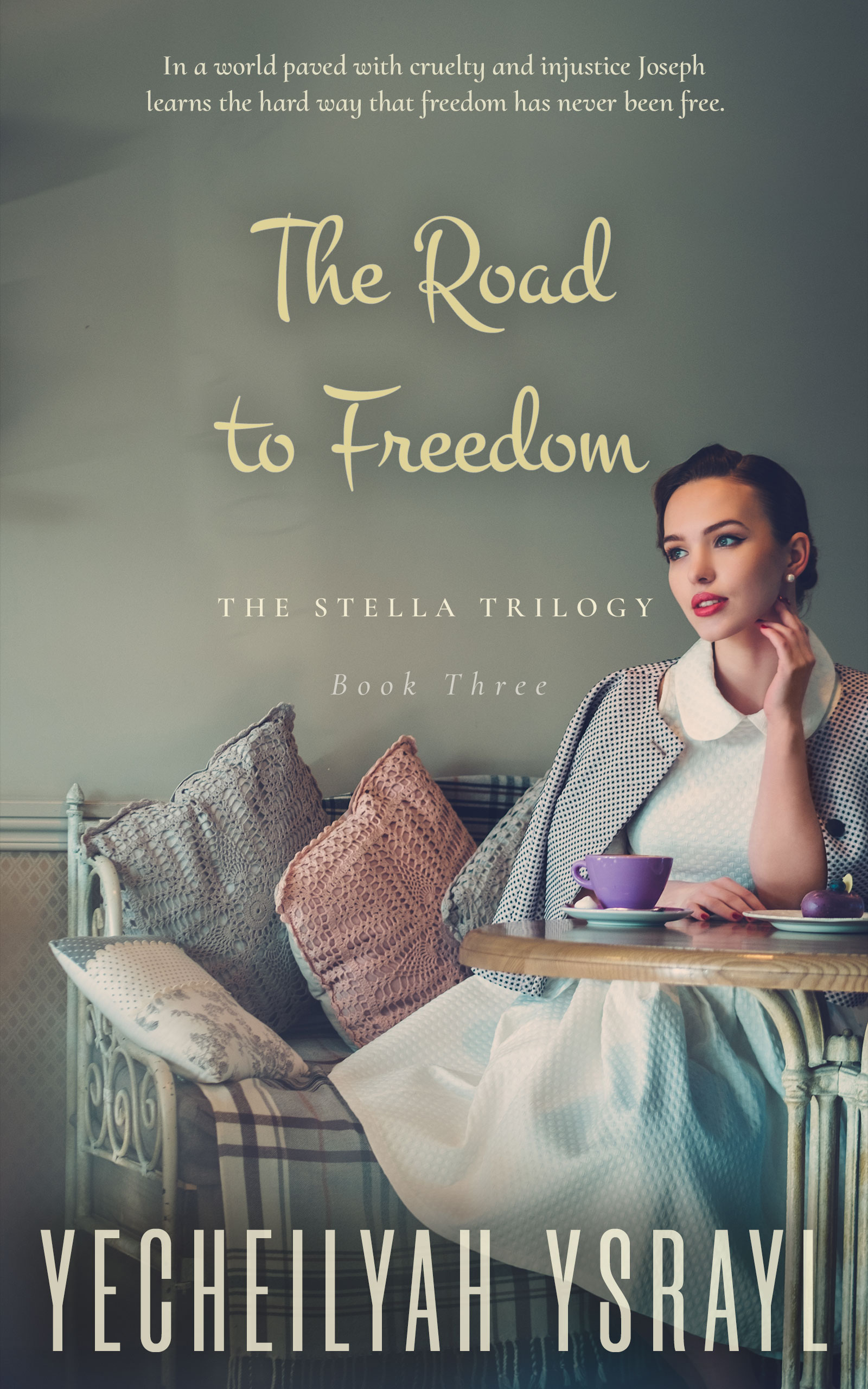

Joseph McNair

Joseph is also conflicted about his mother’s decisions, but goes in another direction. Still under the illusion that he is just a white boy, he nevertheless feels sympathy for the plight of Blacks and fights for their freedom with his friends during the 1960s.

Unlike Edward, Joseph wishes he were Black. He grew up to marry a Black woman named Fae, and together, they have two children, a boy named Michael and a girl named Tanya.

Introducing Tanya and Michael…

Born in the early 90s, Tanya and Michael are the children of Joseph and Fae and are young adults in the early 2000s. They face the challenge of defining themselves in a society shaped by their father’s choices and haunted by the truths Stella once fought to conceal.

In book three, they are small children, but in book four, they are young adults. In his part, we weave together the struggles of a new generation to find their voice, identity, and place in a world still wrestling with its past. The echoes of Stella’s decisions resound, reminding us that even as times change, the threads of heritage and truth remain unbroken.

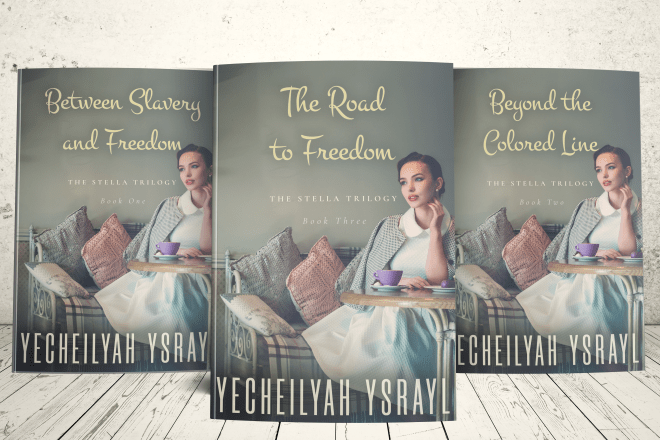

Get Started on The Stella Trilogy!

Book Four: Joseph’s Children

(Working Title)

(WIP/Coming Soon)