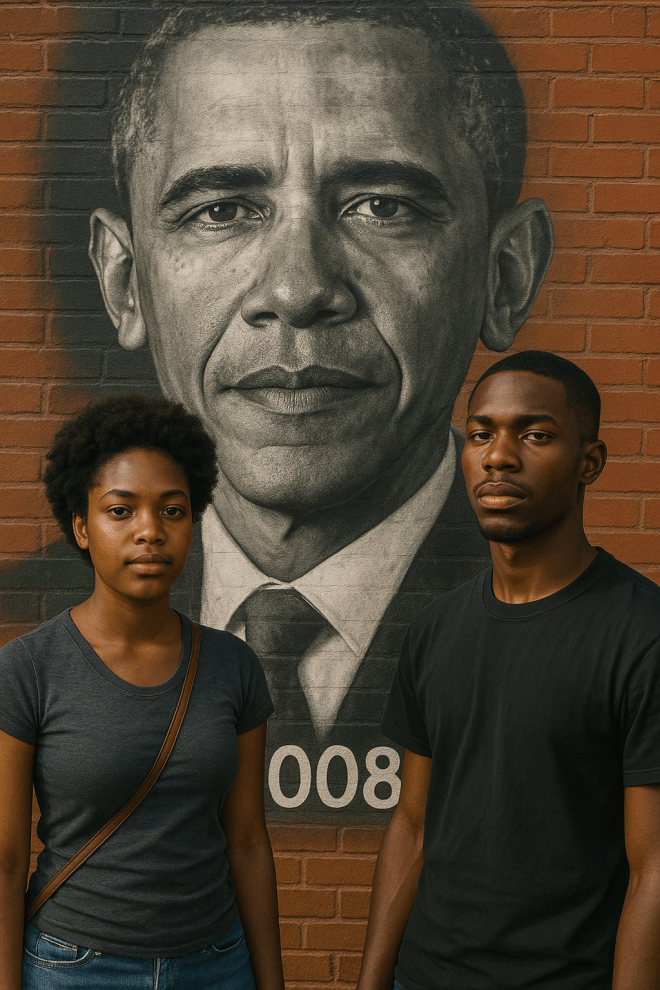

Tanya McNair, dressed in her favorite navy-blue blouse, which bore a faint trace of glitter from the campaign rally a month ago, moved from group to group of the crowded apartment. Her living room was alive with chatter, laughter, and the occasional burst of applause from friends and neighbors whenever a commentator announced another state leaning toward Obama. Tanya looked fondly at the old TV set sitting on the floor beneath the big, flat-screen they were all watching.

The floor model television belonged to her grandmother, Sidney McNair—Mama Sidney to everyone who knew her. Uncle Eddy had bought it after great-grandma Judith passed, back when he and his sisters decided to remain in Chicago a while longer. That was also around the time her father, Joseph, disappeared into what he later called a revolution of self-discovery, also known as abandoning the family until he found himself.

The television had been there through it all.

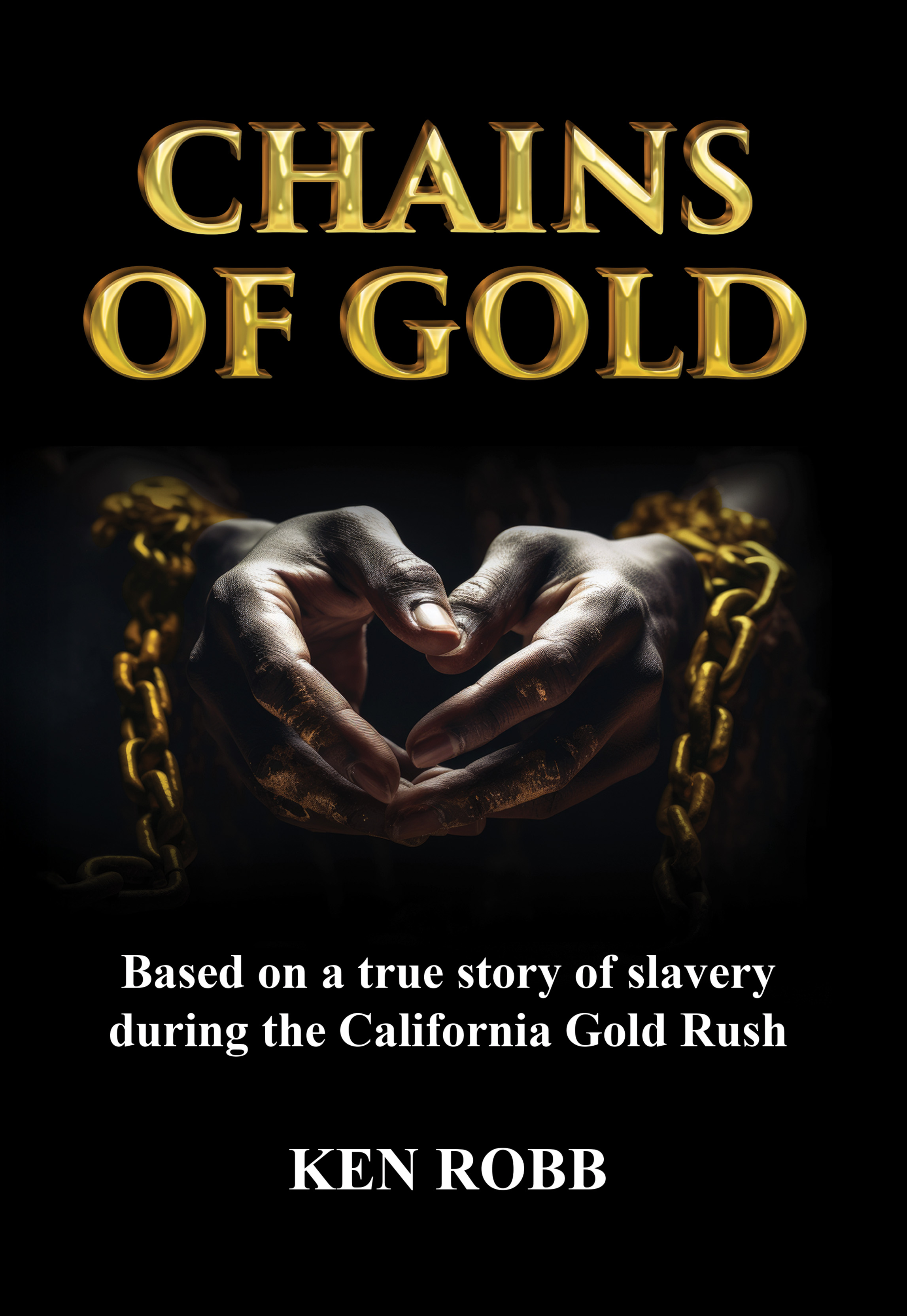

It was the same set where great-grandma Judith—daughter of the great Solomon, son of the first Stella—watched the Black Panthers march down the street in their berets and rifles, demanding the freedom of Huey Newton.

The same screen that flickered quietly in the corner the day Aunt Karen’s boyfriend, Noah, stormed into their lives. Years later, she would name their first and only son after him.

For Tanya, it wasn’t just a piece of furniture but a sacred repository for memories, a portal to her family’s history.

Tanya frowned at the stacks of books on top of it, wondering if she was disrespecting her grandmother by using her TV as a table.

A cheer erupted from the room as the phone rang. Tanya’s heart raced as she ran to answer it without taking her eyes off the flatscreen. So far, Obama was winning.

“Sisss,” sang her little brother.

Tanya raised her eyebrows, “Are you drunk already, Mike?”

“Nah. I’m good. What’s the word?”

Tanya sighed, “Michael, you are not good. I can smell the Hennessy through the phone.”

Mike burst into laughter, and Tanya pulled the phone from her ear. That boy was gonna make her go deaf. “Where are you anyway?”

“I’m handling some business. Why, what’s good?”

“The business you were supposed to be handling is here. What happened to you helping me with the party?”

“The election party? You know I don’t get into alla that,” he said, slurring his words.

“Well, you need to get into it. History is being made. Have you talked with Dad?”

“History? Yea okay. Nah. I ain’t spoke to him today.”

“He was supposed to be coming over.”

“Coming over where?”

“Over here, to the apartment.”

“Not today, he ain’t. He told me he was working on the Malibu.”

“That beat-up old thing?” Tanya sighed. “And I thought you ain’t talk to him?”

“Look, pops don’t wanna hurt yo feelings, but you know the old man don’t vote.”

It didn’t make sense to her. Joseph McNair was born in 1945 and grew up in the ’60s at the height of the Civil Rights Movement. He had heard Dr. King speak, fought segregation with his friends through protest, and was even beaten for trying to integrate at a bus station during the Freedom Rides.

Finding out he really was a mixed Black man and not the white boy he grew up believing himself to be is a history lesson all its own.

And now, as the country waited with bated breath to see if the United States really would elect its first Black President, her father, the revolutionary of the family, didn’t participate in politics?

Joseph McNair was politics!

“Yo T, you there?”

Michael’s voice startled Tanya back to the present, her heart beating a million miles per minute as her guests sat on their hands, quietly waiting on the biggest announcement of their time, the walls echoing with hope.

“Okay, well. I’ll call you back.”