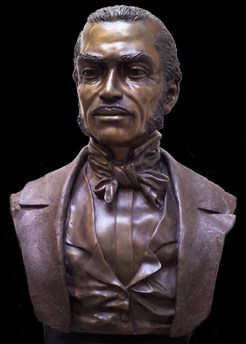

In 1870, the first Black public High School opened in Washington, D.C. or rather, the first recorded school (Aside from Tuskegee Institute–one of the first schools for African Americans financially sponsored by Blacks and Whites but headed by a Black President, the late Booker T. Washington–I do not believe Dunbar was the first High School just as Rosa Parks was not the first to refuse to give up her seat on a bus (LEARN MORE HERE) there is a lot of things that just aren’t recorded.)

The Preparatory High School for Colored Youth (renamed in 1916 to M Street Public School when its location was changed from M Street), was founded in the basement of Fifteenth Street Presbyterian Church by William Syphak, the first chair of the Board of Trustees of the Colored Public Schools in the District of Columbia. According to Dr. Thomas Sowell in an article (100 Years After Dunbar) in 1899, when it was called “the M Street School,” a test was given in Washington’s four academic public high schools, three white and one Black. The Black High School scored higher than two of the three white High Schools. Of course, this isn’t about color or race but is used as an example to highlight the success of all Black Schooling at that time.

Blacks during Segregation were more unified considering many of us had to stick together in order to build communities and schools. For this reason, many all-Black communities, as well as all Black schools, did well. There was a communal spirit among blacks during segregation that sadly deteriorated once we were capable of going outside of ourselves.

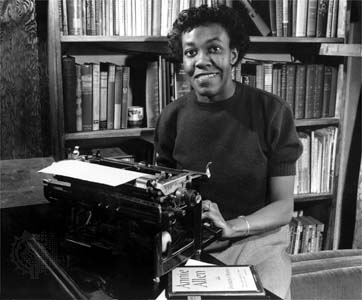

Before Brown vs. Board of Education, Dunbar acquired only the best teachers, many of them with Ph.Ds. and graduated 80% of its students. Among its students: the architect of school desegregation, Charles Hamilton Houston, Elizabeth Catlett, the artist, Billy Taylor, the jazz musician, the first Black general in the Army, the first Black graduate of the Naval Academy, and the first Black presidential Cabinet member, according to Journalist Alison Stewart, author of First Class: The Legacy of Dunbar, America’s First Black Public High School as told to NPR host Cornish on All Things Considered.

In addition, many more, including the first Black woman to receive a Ph.D. from an American institution, the first Black federal judge, and a doctor who became internationally renowned for his pioneering work in developing the use of blood plasma.

The Downfall of Dunbar

Unfortunately, like many Black experiences after integration, Dunbar declined. According to Sowell, senior at the Hoover Institution, Stanford University:

“For Washington, the end of racial segregation led to a political compromise, in which all schools became neighborhood schools. Dunbar, which had been accepting outstanding Black students from anywhere in the city, could now accept only students from the rough ghetto neighborhood in which it was located. Virtually overnight, Dunbar became a typical ghetto school. As unmotivated, unruly and disruptive students flooded in, Dunbar teachers began moving out and many retired. More than 80 years of academic excellence simply vanished into thin air.”

I agree with Sowell only to an extent. I do not think that “unruly and disruptive ghetto students” are responsible for the downfall of Dunbar, but rather the decline in Blacks students being taught by Black teachers concerning Black lives and Black history.

I remember a video interview Maya Angelou gave where she testified that her school was “grand” and many others of the era who described their schooling as a positive experience. Though not given the same quality of learning materials, I believe Blacks got a better education before integration. Not merely because of segregation itself, but rather because it forced us to unify in a way that does not exist today.

In short, we were educating our own. Without teachers and faculty who actually understand them, their struggles and experiences, students can find it harder to adjust. In Angelou’s words, “blacks used what the West Africans in Senegal called ‘Sweet Language'” which is still used today. For example:

“Hey, there” is used as opposed to, “Hi, how are you?”

The Hey is drawn out and spoken with a certain tone of familiarity as sweet language is dependent entirely on tone. The way that Angelou spoke herself was in a sort of sweet language where every word, even if she didn’t mean it to, sounded like poetry.

“Hey, how you?”

This is not grammatically correct or what may be referred to as “proper” and it’s not meant to be. It is the lengthening of the word, the dragging it out and using a loving tone of voice, a caring voice: “Hey.” It is something that Blacks have been doing their entire lives without effort and is something that is mostly understood by other Blacks and while deemed sweet language, I call it a language of love.

This is just one example of the kind of History Israelite, so-called Black, children do not learn in today’s schools.

As the Black teachers moved on, so did Black students interest in learning, or so it seems. Over time, at least three more schools would be named after Dunbar: Paul Laurence Dunbar High School in Baltimore, Maryland, Fort Worth, Texas, and Chicago, IL.

While segregation allowed for inferior educational experiences in some respect (such as torn and used books as opposed to new ones) who is to say that the education itself was inferior? I am more interested in what was being taught behind closed doors. The historical, archaeological, and biblical history of Blacks that I am sure to have never made it in the history books. What really made these students prosper as opposed to the students today?

Dunbar now graduates only 55% of its students according to the 2016 values based on student performance on state exit exams and internationally available exams on college-level coursework, and AP®/IB exams are unranked in the National Rankings. But what do we expect? How do we expect the people who oppress us to also teach us the truth about who we are? If you weren’t being treated right, how do you think that you were taught right?

One thing is for certain, to assume that integration made education for Blacks better is up for debate.